How does a program director chart a path to intellectual leadership – especially if it seems to lead farther away from productivity as a researcher?

I have observed recently that academics have a great deal in common with entrepreneurs. We each have to develop a “brand” to some extent, and we have to promote that brand in order to reap professional rewards. Identifying a clear, and often narrow, set of research interests is a way to consolidate that brand, and consolidating the brand makes it easier to build recognition and get the products we make in front of people. We deal with measures of success that often have little to do with the amount of effort that we expend, we run the risk of letting our work spill over into every realm of life, and we have to know when to push harder and when to let a project go. Also, we may harbor both hopes and fears that luck (or at least the unpredictable alignment of factors that are beyond our control) may determine our success.

Entrepreneurs, however, are not necessarily charged with a mandate to replicate themselves in an upcoming generation of entrepreneurs, and their products and services may still sell like hotcakes even if they do not have discernible applications in the real world or a positive social impact. As academics, we may be able to get away with promoting our own brand, even if we prioritize our own research to the detriment of our research assistants or strive for large numbers of publications without seeking implications for our findings and disseminating them to the stakeholders who might benefit from them.

However, the increasing emphasis on intellectual leadership in higher education and various domains of the humanities and sciences suggests two ways that academics and academia can enhance our measures of achievement: on one hand, we may need to measure the impact of our research and publications more broadly; and on the the other hand, we may need to define the objectives and outcomes of our lives in academia by measures other than research and publications.

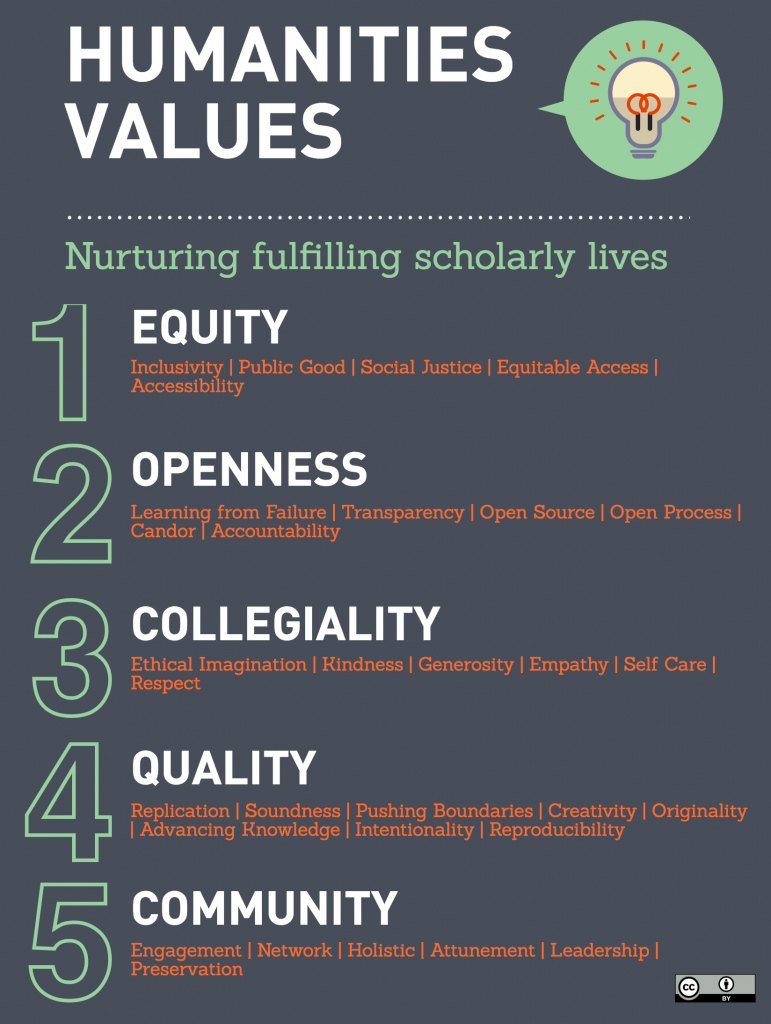

Many of those in leadership positions that impact my work here in the MAFLT and CeLTA have been putting forward definitions of intellectual leadership that promote humane values and align with the vision statement for our college. The Humetrics HSS project, which includes our dean among its team members, promotes the following criteria:

- Equity

- Openness

- Collegiality

- Quality

- Community

In this framework, Quality clearly remains a priority, but its definition and assessment become interconnected with a larger ecology of ideational and interpersonal relationships. The sites below include explanation of these indicators on the Humetrics site as well as short pieces in which our dean, our associate deans, and the director of our academic unit present their views of intellectual leadership and its implications.

Intellectual Leadership Links

HuMetricsHSS – Rethinking Humane Indicators of Success in the Humanities and Social Sciences

About: Humanities Values

Bill Hart-Davidson on Medium

Like an Oak Tree: Considering Pathways for Intellectual Leadership

Sonja Fritzsche’s Leadership Mini-Blog

Cultivating and Evaluating Administrative Intellectual Leadership

Dean Chris Long’s Long View Blog

Recent post: No Quality without Equity

CeLTA Director Felix Kronenberg

Spotlight: Integrative and Applied Research Agenda

I am by nature and training an exploratory and qualitative researcher, and as such I am inclined to engage in projects with many facets and few boundaries that can take huge amounts of time and effort but also speak clearly to the needs and existing awareness of the stakeholders who might take up and apply the findings.

From the beginning of my work as a teacher trainer and applied linguist, I have been concerned with issues of identity, culture and intercultural competence, learning communities, and teacher cognition. Specifically, I am still deeply concerned with heritage learners and learners of critical languages and with providing support for teachers in their intellectual and professional development.

I believe it was Elaine Tarone who advised me that one of the wisest ways forward for me, as someone who is trained as a researcher and wants to continue conducting and carrying out research but who is deeply engaged and frankly booked up with teaching and administration, that I should keep my research endeavors close to the work that I am already doing. The work that I do with language teachers is inherently conducive to studying teacher cognition and the emergence of their expertise over time through apprenticeship models of learning, and I do want to keep going in that direction, as well a few other areas that stem from my prior research and my work as a teacher educator.

These topics all lend themselves well to what the HuMetricsHSS project considers to be “humane indicators of excellence in the humanities and social sciences”: Collegiality, Quality, Equity, Openness, and Community. Whether I am able to free up the bandwidth to engage in extensive research projects or not, my steps forward need to be guided by definitions of excellence like these. The measures of success that I strive toward, both for the field and for my own integrity, need to aim toward intellectual leadership by engaging with my own communities of practice, valuing transparency and “equitable access to research,” and also maintaining a habit of “kindness, generosity, and empathy toward other scholars and oneself” (humetricshss.org/about/).

By those criteria, any statement of my own research interests and agenda reflect a larger mission statement. Like an entrepreneur, I need to consolidate my “brand” as an individual scholoar, but I also need to manage my efforts and affordances so that I can thrive in the years ahead and therefore have the strength to help others thrive with me.